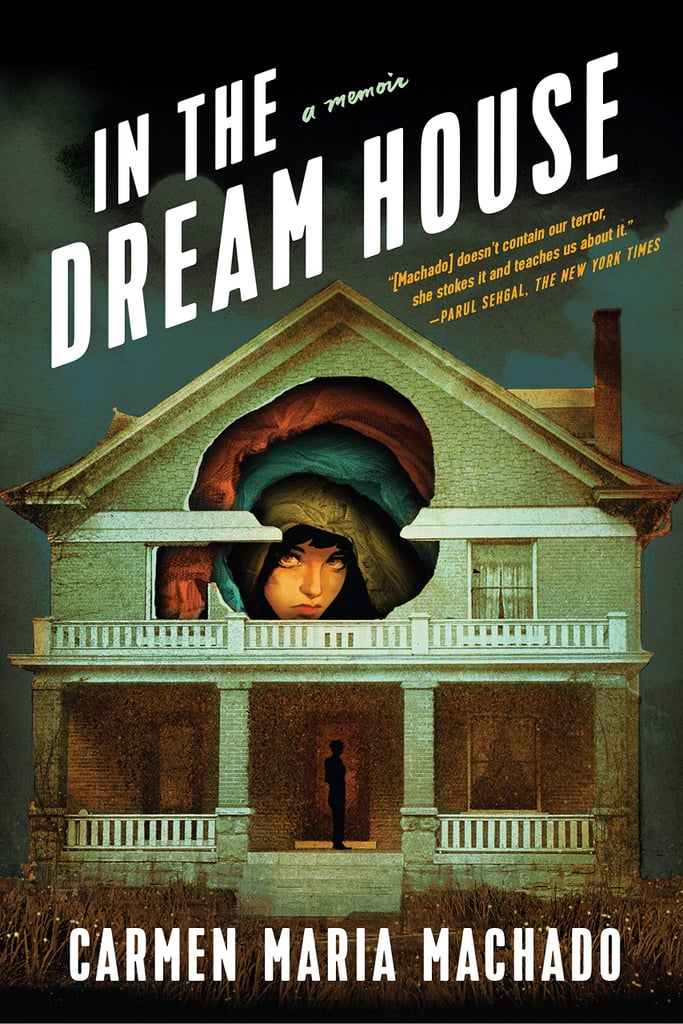

In The Dream House By Carmen Maria Machado

In the Dream House is a memoir showing domestic abuse in a queer relationship. The author describes her trauma in poetic prose that is so freaking haunting. Every aspect of her story resonated so deeply with me, and there's a reminder here that being queer doesn't make you good or bad. To discuss all of this, I spoke with Carmen Maria Machado, author of the memoir In The Dream House, the collection of strange tales Her Body And Other Parties, and the graphic novel The Low, Low Woods. Carmen Maria Machado is the author of Her Body and Other Parties, which was a finalist for the National Book Award, and In the Dream House, which was the winner of the Rathbones Folio Prize. She is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship and is the Abrams Artist-in.

Reviewed by Erin Becker

Published:Everything tells a story.

Societies tell stories about power and freedom, who deserves them, and why. Relationships tell stories, especially as they end: who is the hero, who is the victim, who is the villain? People tell stories, too. About themselves, about others, about the way the world works. They do this to make things make sense. To justify their actions. To get through the day.

In these narratives, people learn and grow, win and lose, hurt each other, reconcile.

They dream. They exist.

But what happens when you’re left out of the story, even your own story, altogether? Maybe you feel somehow wrong or impossible, or invisible, even to yourself. Maybe you start to wonder whether you do, in fact, exist.

The prologue of Carmen Maria Machado's memoir, In the Dream House, defines the concept of archival silence: “sometimes stories are destroyed, and sometimes they are never uttered in the first place; either way something very large is irrevocably missing from our collective histories.” Queerness itself has been left out of the narrative for much of history, and even now, as Machado notes, abuse in queer relationships is still a largely untold story. The CDC acknowledged, in its 2010 survey of intimate partner violence, that “Little is known about the national prevalence of sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence” amongst LGBTQ couples. Ten years later, statistical, academic, and societal factors continue to complicate the understanding of both the prevalence and the nature of abuse in same-sex relationships, particularly those between women. Issues affecting the data include small sample sizes in many relevant research studies; reluctance amongst lesbians and bisexual women to report violence perpetrated by members of their own community; and even heteronormative language used by staff at domestic violence shelters, who may assume all abusers are men.

Machado reckons with this archival silence –– the unknown statistics, the sparse and spotty data, the unreported incidents, the help that comes bundled with erasure –– by telling her own story. “Our culture does not have an investment in helping queer folks understand what their experiences mean,” she writes. Here, she tries to make this meaning anyway.

In the Dream House tracks Machado’s relationship with her unnamed ex. The two women meet in Iowa City, where Machado is studying for her MFA. They begin a turbulent relationship that passes through many phases –– polyamorous, monogamous, long-distance, troubling, downright scary –– but that first night, Machado is smitten: “she touches your arm and looks directly at you and you feel like a child buying something with her own money for the first time.” They have sex and take road trips. They write and go to parties and plan a version of the future together. They fight. A lot. Machado cries, a lot. Throughout, Machado does a brilliant job conveying all the ways in which the “woman in the Dream House” was alluring to her, and, despite the emotional and –– at times –– physical abuse, her very real grief when their relationship ended. Even after all that awfulness, there’s the inevitable nostalgia: “You occasionally find yourself idly thinking about how it could have gone right.” And there’s the terrible sense of loss, even amidst all the ugliness: “Afterward, I would mourn her as if she’d died, because something had: something we had created together.”

The story is in turns heartbreaking, sensual, and disturbing. But perhaps most significant of all is the way Machado chooses to tell it. Rather than settling on one form, point of view, or genre, Machado writes In the Dream House in a series of short, dense, and gleaming chapters that play with different genres and literary tropes, or reference different mediums. With titles like Dream House as Picaresque, Dream House as Bildungsroman, Dream House as Road Trip to Everywhere, and Dream House as Choose Your Own Adventure, each explores an aspect of Machado’s relationship with the unnamed woman or the circumstances that led to it. Each tries to make sense of the experience in a new way. Because most of the memoir is written in second person, with the narrator addressing her former self: you, you, you, the book feels both intimate and vaguely instructional, as though––through these varied approaches to storytelling––the narrative is trying to do the work of meaning-making for queer people that the culture at large, in Machado’s view, has long failed to do.

In one particularly compelling section, Machado talks about having no example for what’s normal when dating a woman, a truth that contributed to the difficulty of recognizing and naming what was happening to her. “You trust her,” Machado writes of her ex, “and you have no context for anything else.” Machado touches again on this lack of context in a passage where she describes realizing, many years later, that she had a crush on a classmate when she was young. “I didn’t know what it meant to want to kiss another woman,” she writes, recalling how she would stare at her classmate’s freckles. Years later, she figured it all out… “But then, I didn’t know what it meant to be afraid of another woman. Do you see now? Do you understand?”

Machado is an accomplished horror writer whose debut, Her Body and Other Parties, won the Shirley Jackson Award, was a finalist for the National Book Award, and was widely credited with blending horror with science fiction, dark comedy, and a sensibility both literary and grotesque. In the Dream House is neither fiction nor horror, but here Machado still manages to effectively communicate the psychological trauma and the utter creepiness of feeling “trained to be found” by an abusive partner who seems “trained to find you.” By the memoir’s end, any reader can understand what it’s like to be afraid of a woman.

In this way, one of Machado's achievements with In the Dream House is the vividness with which she fleshes out the trauma that remains in the wake of an abusive relationship. Yet, despite the disturbing reality at its core, the book also feels deeply hopeful. This may be because the memoir’s structure –– the use of so many different narrative forms –– is itself a hopeful reality. In a patchwork of traditions and genres, Machado has begun the work of constructing this same context that she once lacked. Interestingly, Machado addresses this choice of narrative structure within the text, positioning it not as an aspirational act, but as something of a last resort: “I broke the stories down because I was breaking down and I didn’t know what else to do.” But from an audience perspective, each new genre Machado explores –– Fantasy, Exercise in Style, Comedy of Errors, Cautionary Tale –– also feels like a small act of resilience: like the pulling up of a chair to a new literary table. With each piece of this story, Machado claims a bit of space for women who love women, in a literary canon that has not always made space for this love. It’s a response to the archival silence. A direct and noisy one, at that.

With In the Dream House, Download adobe illustrator cc 2020 mac. Machado offers a model for creating a new language out of the messy bric-a-brac of the everyday. Here Machado is a victim, yes, but she also becomes namer, author, narrator, and protagonist––and not just in one story or genre, but many. By the end of the book, Machado reclaims her own first person: “Many years later, I wrote part of this book in a barn on the property of the late Edna St. Vincent Millay.” Not coincidentally, it’s the act of writing that becomes transformational. Machado is subject now, rather than object. She is no longer a “you,” but once again an “I.” It is through writing, in the end, that Machado grasps her way toward a reimagining of what it means to be queer, resilient. To become the protagonist in a tapestry of stories, and to make them all one’s own.

Erin Becker is a freelance writer, editor, and translator. She is an MFA candidate at Vermont College of Fine Arts and a graduate of the English and Creative Writing program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

LISTENHEREVIA SOUNDCLOUDORONApple Podcasts • Spotify • Breaker• Anchor

FRIENDS: Do you find this podcast meaningful? Support it! This podcast is only possible because listeners like you support it. Do contribute to my mission by supporting Against Everyone With Conner Habib onPatreon! Thank you so, so much.

Buy Carmen’s books and the books mentioned on/related to this episode via my booklist for AEWCH 149 on Bookshop.org. Bookshop.org sources from independent bookstores in the US, not a big corporate shipping warehouse where the workers are treated like machines. Plus when you click through here to order, the show gets a small affiliate kickback!

Friends,

The French psychoanalyst and philosopher Jacques Lacan once said, “there is no other good than the one that can pay the price of the access to desire.”

There’s a lot about this statement, which is, like a lot of what Lacan said, a riddle – but one thing in it – paying the price of access – so our desires are not accessible? So we must lose something, give something to meet them? To see them? To talk about them?

To discuss all of this, I spoke with Carmen Maria Machado, author of the memoir In The Dream House, the collection of strange tales Her Body And Other Parties, and the graphic novel The Low, Low Woods.

I think what’s really interesting to both of us, and this comes up quite a bit – is how desire functions, how it is somehow always ahead of us, appearing and disappearing like a friend or an enemy on the path in a fairy tale. Sometimes it gives something to us that is useful later on. A key, a sacred object, a weapon. Sometimes it gives us a gift that leads us to being stuck. Like the fairy market where someone accepts the gift of an apple from the goblin, eats it, and wakes up 100 years later, if they wake up at all. Sometimes it has a strange shape, it frightens us.

Why should desires be like this? How do they know us, in a way, before we know ourselves?

This is a conversation that finds proximity to creation, to danger, to repetition, to the abuse that Carmen writes about in her memoir In The Dream House,and to the abuse I wrote about in my essay ,”If You Ever Did Write Anything About Me, I’d Want It To Be About Love“.

How do we talk about the desire and the horror in abusive relationships while still holding the abuser accountable. How do we make the necessary move of accountability while not reducing the complicatedness of the encounter and the relationship?

Again and again, Carmen and I touch on desires and on storytelling – almost like we’re knocking on wood to allow ourselves to go forward in difficult conversation.

The Resident Carmen Maria Machado

What do we sacrifice to know our desires?

What are the prices of following our desires

Of not giving way to them?

Of not giving ground to them?

In The Dream House Carmen Maria Machado Amazon

If all that sounds dark and complex, well, it is. but this is also such a warm and friendly episode. With lots of laughter and curiosity and affinity.

I’m so happy to share this episode with you.

ON THIS EPISODE

- The way desire knows itself before you know what it is

- Why is the fox from Robin Hood so hot

- Evading the temptation of metaphor when we read

- The response to the subconscious is determines the genre of writing

- Horror as spiritual narrative

- H.P. Lovecraft’s mission of mercy

- Sexuality as a genre

- The imagination of the abusive partner after you’ve left them

- The missing language of understanding for the person who has been abused

- Why we need to talk about resilience

- The importance of meta-devices and melodrama

- The Law & Order SVU-niverse

In The Dream House By Carmen Maria Machado Youtube

SHOW NOTES

• For more on Carmen go to her website (which has a badass picture of her in a chair). Here’s an interview with Carmen that goes horrifically wrong on Electric Lit. Here’s Carmen talking about haunted houses and horror movies on the American Hysteria podcast. And if you’d like to read one of her stories, here’s the early version one we reference the most, “The Husband Stitch“.

Dream House Carmen Maria Machado

• My essay from 2010 “Looking at Men” describes the clouded shower glass incident.

• McArthur Award-winning writer Kelly Link comes up a lot on this episode. Have you listened to AEWCH 44 with Kelly, Jordy Rosenberg, and me? It’s awesome. Also, here’s Kelly’s essay about the “silent partner.“

• Here’s an interview with the great Argentine writer, César Aira.

• It looks like Grant Morrison’s Seaguy is not available on bookshop.org, so here it is from that, uh, other place.

• If you haven’t read Susan Sontag’s essay, “Against Interpretation,” read it, friends. And if you have read it, read it again. Same goes for H.P. Lovecraft’s essay, “Supernatural Horror in Literature“.

• And the Lovecraft quote is, ““The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.”

• Here’s my essay “If You Ever Did Write Anything About Me, I’d Want It To Be About Love” about the boyfriend who beat me up, which is mentioned at the end of Carmen’s memoir (and through which Carmen and I first communicated).

In The Dream House Audiobook Carmen Maria Machado

• I love author Sara Maria Griffin’s appearance on AEWCH 93. It remains one of my very favorite episodes.

In The Dream House By Carmen Maria Machado Movie

• I have not yet read Jeannie Vanasco’s Things We Didn’t Talk About When I Was A Girl but I definitely will now. I also (forgive me, Father!) have not yet seen Fleabag. I will, I will, I will!

• Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s movie The Bitter Tears of Petra Van Kantis one of the best films ever made. And also watch Lars Von Trier’s Dogville for another sort of disorientation.

In The Dream House Carmen Maria Machado Epub

Until next time friends, follow your desires!

XO

CH